Typically our bodies limit iron absorbed in our digestive tract. In some people, the ability to limit iron absorption is compromised, resulting in excess iron stored in the body (especially in the heart, liver or pancreas). Over time, excess stored iron leads to organ damage, including liver cirrhosis. Signs of iron overload may include weakness or chronic fatigue, early onset arthritis, abdominal pain, decreased sex drive, bronze or grey skin discoloration.

Typically our bodies limit iron absorbed in our digestive tract. In some people, the ability to limit iron absorption is compromised, resulting in excess iron stored in the body (especially in the heart, liver or pancreas). Over time, excess stored iron leads to organ damage, including liver cirrhosis. Signs of iron overload may include weakness or chronic fatigue, early onset arthritis, abdominal pain, decreased sex drive, bronze or grey skin discoloration.

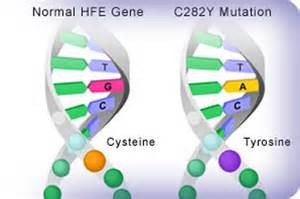

A known trigger of iron overload is a mutation of the HFE gene or hemochromatosis. HFE gene mutations are not uncommon, especially among people of northern European descent. But not all people with the HFE gene mutation get into trouble with iron overload. And not all people with high iron levels have an HFE gene mutation. Research is ongoing to determine other causal factors that influence absorption of iron, including other genes. It may seem counter-intuitive, but over-consumption of dietary iron has not been found to play a big role in iron overload.

A known trigger of iron overload is a mutation of the HFE gene or hemochromatosis. HFE gene mutations are not uncommon, especially among people of northern European descent. But not all people with the HFE gene mutation get into trouble with iron overload. And not all people with high iron levels have an HFE gene mutation. Research is ongoing to determine other causal factors that influence absorption of iron, including other genes. It may seem counter-intuitive, but over-consumption of dietary iron has not been found to play a big role in iron overload.

Hepcidin, a hormone produced by the liver, appears to be the master regulator of iron homeostasis. It regulates (inhibits) iron transport across cells, thereby preventing excess iron absorption and maintaining normal iron levels within the body. Important research is ongoing about the role and regulation of hepcidin and about other causes of iron overload.

Hepcidin, a hormone produced by the liver, appears to be the master regulator of iron homeostasis. It regulates (inhibits) iron transport across cells, thereby preventing excess iron absorption and maintaining normal iron levels within the body. Important research is ongoing about the role and regulation of hepcidin and about other causes of iron overload.

Iron in the blood (serum iron or ferritin) is an indicator of overall iron levels. A ferritin level between 50 and 150 is usually safe. Very high levels may be cause for concern (low levels can lead to anemia and tiredness). Removing blood (phlebotomy) causes the body to manufacture new red blood cells. Iron required to make the new cells is drawn from the body’s stores (i.e., in the liver, heart or pancreas), thereby reducing dangerous stored iron.